Say you've got a new idea for a device that would improve aviation in some manner, and say you've got the desire to see it through to hitting the market and actually being implemented by real-world customers. How do you go about this? What's the next step? Well, we've got a real-world case study right here for you, because as it happens, AdvancedPrimitive.com is run by a rocket scientist. Yes - the kind that has been waiting for years for someone to say - who do you think you are, a rocket scientist or something?

Let's switch to the first person - it'll make a lot more sense...

As a long time fan of aviation of all shapes and sizes, a perpetual student pilot with time in several different LSAs, a holder of a BS in Aerospace Engineering, and as someone currently working with the Federal Aviation Administration, I'm very much someone who is looking at coming up with new ideas to fit the industry. My specific area of interest is General Aviation, light to medium size fixed-wing aircraft, and one day I was thinking about the lowly Vortex Generator - one of those little ridges that you find near the leading edges of (mostly) STOL aircraft.

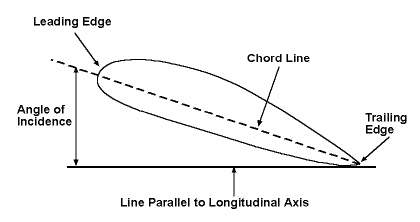

The basic theory of what vortex generators do is quite simple and has been known in aviation for many many years. Just like the wingtip vortex that you can see behind an airliner landing on a foggy day, it's the effect of high and low-pressure air mixing beyond the end of a lifting surface.

Placing a VG, which is basically a tiny wingtip angled into a permanent angle of incidence, has the effect of that little wingtip vortex pushing the boundary layer of air flowing along the wing surface toward that surface. Why is this good? Well, at high incidence angles the flow begins to separate from the surface, which creates turbulence, which in turn creates more drag and less lift (assume that at that point most of the lift goes away).

What happens at that point when the wing at a high incidence angle experiences this separation, is the loss of most of the lift, which results in the nose of the aircraft dropping. This is not a big deal when you have the altitude to recover and keep the ball centered (fly in a coordinated manner - where the nose of the plane points in the direction of motion) so as not to enter into a spin. The problem is that this is a condition associated with slow flight, and the place where aircraft typically slow down, or fly at less than cruise speed, is when taking off or landing - at low altitude, with little room to recover. NTSB statistics of aircraft accidents and fatalities reflects this, sadly, and every year there are many stall-spin accident fatalities that occurred when low and slow led to loss of control and a crash.

From 17 to 28 % of all fatal fixed-wing accidents where the result of a stall that was followed by loss of control. That is a huge number! How many lives were saved in automobiles with the mandatory use of seat belts? General aviation is much smaller in scale than public use of cars, but what is the cost of 50 lives saved per year? 100? Whose lives would be saved, btw? People taking part in general aviation are generally very productive individuals - doctors, business owners, politicians (there are exceptions, I'm sure), and other above-average-net-worth individuals who create jobs, invest in other industries, etc. That is a separate issue, though, so let's stick to the main subject - the lowly vortex generator.

Why isn't EVERYONE installing a vortex generator on EVERY light and medium size aircraft? Well, there are reasons - cost and cost. First is the direct cost - purchasing a set of VGs for a mainstream certificated aircraft (Part 23 aircraft - think of a Cessna 172, for example) costs over $2,000. What's the other cost? Fuel. Anything you add to the skin of an aircraft adds drag. More drag = more power needed to fly at the same cruise speed, which in turn means more fuel to cover a given distance and thus more money spent per mile. Now, what if we could get the best of both world - the full positive effect of the VG and none of the fuel-wasting cost of that VG when flying at cruise speed, where the VG does absolutely nothing to improve safety? The people currently installing VGs generally do so because they only want to fly low and slow - the STOL community. The benefit of trimming 4 to 8 knots when landing more than makes up the difference for losing 3% to 5% of cruise efficiency.

If general aviation Part 23 aircraft require an STC from the FAA to install vortex generators, which in turn creates a hugely inflated retail price, who can benefit from VGs at lower cost and without any government regulations? That would be the experimental and ultralight community, where the owner can perform own maintenance and install parts as they see fit. The retail cost of a non-STCd vortex generator set drops by a factor of 10, from over $2,000 to about $200.

Getting back to the subject, how do we get the best of both worlds? Full effect of the VG at low speed and no loss of efficiency at cruise? Simple. Make that VG hide when you don't need it. That's the idea that I got and what got me started down the road of getting a patent and now prototyping the idea on sub-scale test models. I am currently marketing my idea under the name Speed Flex VG, and you can get more info at https://SpeedFlexVG.com.

What does sub-scale testing look like?

Everyone tests in sub-scale to flush out any fundamental problems that can be resolved before upscaling and investing more money in research. NASA does it with its X-57 and even built an autonomous 60% scale Cub. In my case, the plan for validating my theory is to fly a remotely-piloted, then an autonomously-piloted UAV, then to install the SpeedFlex VG on Experimental and Ultralight aircraft and run it in a wind tunnel to precisely quantify the benefits. At that point in time I will begin sales and distribution to more Experimental and Ultralight owners and to approach OEMs to help me receive an STC. On the patent front, the SpeedFlex VG is currently patent pending, and a full patent will be forthcoming in the Spring of 2022.

The first UAV flown had standard VGs installed as a baseline testcase. Incidentally, since designing and creating these miniature VGs in Fusion360 and Creality 3D printers, I am considering distributing my SpeedFlex VGs to fixed-wing UAV owners at some point in time.